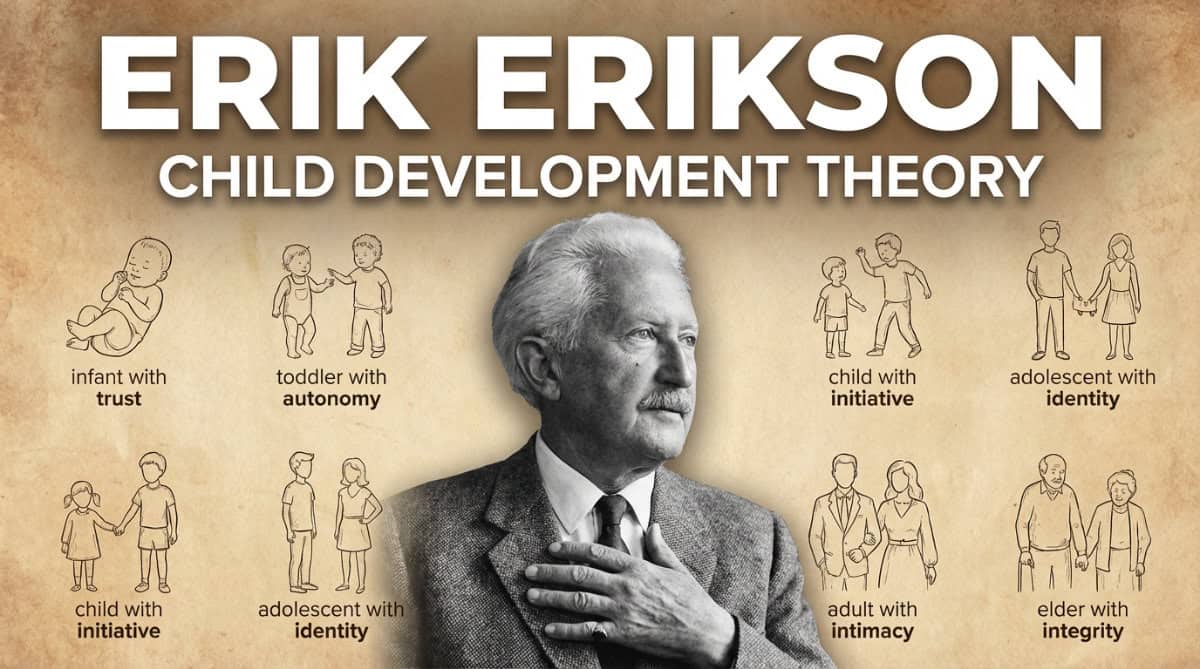

Erik Erikson didn’t just study how children grow – he mapped the entire emotional journey of being human. From the infant who learns whether the world is safe to the teenager wrestling with “Who am I?”, Erikson showed that our personalities aren’t set in stone at age five. They develop through predictable crises throughout our entire lives.

His eight stages of psychosocial development remain one of the most influential frameworks in child psychology. Unlike earlier theorists who focused solely on childhood, Erikson recognised that parents are also developing. That frazzled mother wondering if she’s doing enough? She’s navigating her own developmental stage while guiding her child through theirs.

For Singapore parents balancing cultural expectations with modern parenting approaches, Erikson’s framework offers something rare: a roadmap that acknowledges both individual growth and social relationships. His stages explain why your toddler suddenly refuses help with everything (autonomy development) and why your Primary 6 child obsesses over grades (industry versus inferiority). His work showed that healthy development at each stage builds the foundation for the next.

Early Life & Background

An Identity Formed Through Confusion

Erik Homburger was born in Frankfurt, Germany in 1902 to a Danish mother, Karla Abrahamsen. He never knew his biological father—a fact his mother kept secret for years. When Erik was three, Karla married paediatrician Theodor Homburger, who raised Erik as his own son.

The family told Erik that Theodor was his biological father. But something didn’t add up. Erik was tall and blonde with blue eyes. His stepfather and the Jewish community they belonged to were predominantly dark-haired. At temple, other children teased him for looking Nordic. At his Danish school, classmates called him Jewish.

This early experience of belonging fully to neither world would profoundly shape his life’s work. The question “Who am I?” wasn’t just theoretical for Erik. It was personal.

The Artist Who Became a Psychoanalyst

Rather than pursue traditional academics, young Erik studied art and wandered through Europe. He had no clear direction. He taught art at a progressive school in Vienna, where wealthy parents sent their children for psychoanalytically-informed education.

There, he met Anna Freud, daughter of Sigmund Freud. She was developing child psychoanalysis as a distinct field. Anna saw something in the young art teacher; a natural gift for understanding children. She invited him to train as a child analyst.

Erik underwent analysis with Anna Freud herself. He studied psychoanalytic theory while teaching and observing children daily. He married Joan Serson, a Canadian dancer and artist who would become his lifelong collaborator.

Escape and Reinvention

By 1933, the rise of Nazism made Europe dangerous for Jewish families. The Eriksons fled to the United States with their young children. Erik settled in Boston, where he became the city’s first child psychoanalyst.

In America, he faced another identity question: his name. “Erik Homburger” sounded too German in a country at war with Germany. He chose a new surname – Erikson; literally “Erik’s son.” Some interpreted this as claiming to be his own father, finally resolving the question of paternity that had haunted him.

This reinvention proved fitting. Erik Erikson would spend his career studying how people form and reform their identities throughout life.

Major Contributions

Eight Stages That Changed Everything

In 1950, Erikson published “Childhood and Society.” The book introduced his eight-stage model of psychosocial development. Each stage presents a developmental crisis, not a disaster, but a turning point where growth can go in healthy or unhealthy directions.

The infant faces trust versus mistrust. If caregivers respond consistently to their needs, babies learn the world is reliable. This foundational trust allows them to explore later. When care is unpredictable or harsh, infants learn the world is dangerous and unreliable.

Toddlers tackle autonomy versus shame and doubt. They want to do everything themselves badly. Parents who balance freedom with gentle limits raise confident children. Those who criticise every mess or rush in to help create children who doubt their abilities.

Preschoolers work through initiative versus guilt. They ask endless questions and launch ambitious (often impossible) projects. When adults encourage their curiosity rather than shut it down, children develop purpose and creativity. Excessive criticism teaches them that their ideas are foolish.

School-age children face industry versus inferiority. They compare themselves to peers constantly. Success in schoolwork, friendships, or activities builds competence. Repeated failure or harsh criticism creates lasting feelings of inadequacy.

The Identity Crisis He Named

Adolescents face identity versus role confusion. Erikson coined the term “identity crisis” to describe this stage. Teenagers ask: Who am I? What do I believe? Where do I fit?

Erikson knew this crisis intimately. His own adolescence was marked by confusion about his heritage, his future, his place in the world. He transformed that personal struggle into a theoretical framework that explained millions of teenagers’ experiences.

The adolescent who successfully navigates this stage develops fidelity—the ability to commit to values, people, and goals. Those who remain confused may drift, unable to commit to relationships or directions.

Development Doesn’t Stop at Twenty

Erikson’s genius was recognising that development doesn’t stop at puberty. Young adults must then balance intimacy versus isolation in relationships. Can they form deep connections without losing themselves? Or do they remain isolated, protecting their newly-formed identity?

Middle-aged adults face generativity versus stagnation. They ask: How can I contribute? What will outlast me? For many, parenting answers this question. For others, it’s creative work, mentoring, or community service. Stagnation feels like going through the motions without real purpose.

Finally, older adults reflect on their lives, achieving either integrity or despair. Did I live well? Do I have regrets? Can I accept my life as it was? Wisdom comes from accepting both the triumphs and failures of one’s journey.

Culture Shapes Development

Erikson studied the Sioux tribe in South Dakota and the Yurok people in Northern California. He observed how culture profoundly influences personality development. A Sioux child learned different virtues than a European child, yet both followed similar developmental patterns.

This cross-cultural work distinguished Erikson from his mentor, Sigmund Freud. Where Freud saw universal, biologically-driven stages, Erikson saw cultural variation. The basic developmental crises were universal. How they manifested and resolved depended on cultural context.

For parents raising children across cultures, common in Singapore’s multicultural society, this insight matters. The stages are the same. How you support your child through them can incorporate your cultural values.

Practical Applications

Building Trust in the First Year

Erikson’s first stage explains why sleep training debates get so heated. Responsive parenting during infancy isn’t spoiling, it’s building trust. When babies cry and parents consistently respond, infants learn the world is safe and reliable.

This doesn’t mean perfect parenting. It means good enough. You’ll have nights when you’re too exhausted to respond immediately. That’s human. Consistent responsiveness over time builds trust, not perfection in every moment.

Singapore parents often worry about creating overly dependent children. Erikson’s research suggests the opposite. Babies who develop strong trust become more confident explorers. They can venture out knowing their secure base remains.

Supporting Toddler Autonomy Without Losing Your Mind

The terrible twos aren’t terrible—they’re transformative. Your toddler insisting on putting on their own shoes (backward, on the wrong feet, taking twenty minutes) is developing autonomy. This is healthy development, even when it makes you late for work.

Create safe spaces for messy independence. Let them pour their own water, even when half ends up on the table. Offer choices between acceptable options: “Red shirt or blue shirt?” This builds decision-making skills without daily power struggles over whether they wear clothes at all.

HDB living makes this challenging. Small spaces mean fewer areas where toddlers can safely make messes. Designate one zone where spills are acceptable. A washable mat in the kitchen transforms cleaning anxiety into learning opportunity.

Shame develops when adults react with disgust or anger to normal toddler mistakes. The child who spills milk and faces screaming learns that trying new things brings humiliation. The child whose parent calmly hands them a cloth learns that mistakes can be fixed.

Nurturing Initiative in Preschoolers

Four-year-olds announce they’re building a rocket ship to the moon. They’ll use every cushion you own, all the toilet paper, and somehow your expensive moisturiser.

Erikson would say: let them (within reason). Initiative develops when children can pursue their ideas. Set boundaries around safety and truly valuable items, but give them materials and space to create.

Ask questions about their projects. “How will the rocket fly?” This encourages planning and problem-solving. “What will you do when you reach the moon?” extends their imaginative thinking.

Excessive criticism or impatience teaches children that their ideas aren’t valuable. The preschooler whose ambitious projects always get shut down learns guilt instead of initiative. Better to have messy rooms and confident children than pristine homes and timid ones.

Building Industry in Singapore’s Competitive Environment

Singapore’s education system creates particular challenges for the industry versus inferiority stage. Children naturally compare themselves to classmates. Some handle academic pressure well. Others develop deep feelings of inadequacy when they don’t match their peers.

Erikson’s framework suggests balancing academic achievement with other competency areas. The child struggling with math might excel at art, sports, or helping others. Recognition across multiple domains builds a resilient self-concept.

Teach effort over outcome. “You worked hard on that project” builds industry better than “You’re so smart.” Competence comes from knowing that sustained effort produces results, not from being naturally talented at everything.

When your Primary 4 child comes home discouraged because their friend scored higher on a test, acknowledge the feeling without dismissing it. “It’s frustrating when someone else does better. What helped you understand the material? What could you try differently next time?” This builds problem-solving and resilience.

Legacy & Ongoing Influence

Reshaping How We See Human Development

Erikson’s eight stages became the foundation for understanding human development across the lifespan. Before Erikson, most developmental psychology focused exclusively on childhood. Freud’s stages ended at puberty. Piaget studied cognitive development through adolescence but didn’t address emotional or social growth in adults.

Erikson showed that personality develops throughout life. Parents aren’t finished products raising works-in-progress. They’re developing alongside their children. This reframed parenting from a task you either succeed or fail at to a mutual growth process.

His work influenced attachment theory, identity development research, and therapeutic approaches for all ages. Mary Ainsworth’s attachment research validated Erikson’s claim that early responsive caregiving shapes later relationships. James Marcia expanded Erikson’s identity stage into four statuses (achievement, moratorium, foreclosure, diffusion) that explained different paths through adolescence.

Institutions Carrying His Work Forward

The Erikson Institute for Early Childhood in Chicago was named in his honour. It trains educators and therapists using developmental frameworks grounded in his stage theory. The institute emphasises that early childhood education must address children’s social and emotional needs, not just cognitive skills.

The Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families in London continues applying psychoanalytic developmental approaches to child mental health. Their work reflects Erikson’s insight that understanding developmental stages helps clinicians support children struggling with anxiety, trauma, or behavioural challenges.

Joan Erikson, Erik’s wife and collaborator, continued developing his work after his death in 1994. She added a ninth stage to the model, addressing the very old age that Erik hadn’t lived long enough to fully theorise. This ninth stage involves transcending the physical decline of extreme old age while maintaining integrity.

Modern Research Building on His Foundation

Contemporary researchers have expanded and refined Erikson’s stages. Cross-cultural studies confirmed his basic framework while identifying cultural variations in how stages manifest. Japanese researchers found that the autonomy stage looks different in collectivist cultures, where interdependence is valued over independence. Yet the developmental need for appropriate autonomy still exists.

Digital age researchers apply Erikson’s identity development concepts to online persona creation. Adolescents now navigate identity formation across physical and virtual worlds. They ask “Who am I?” on Instagram, TikTok, and Discord servers. The platforms are new. The developmental crisis is timeless.

Neuroscience research has begun identifying brain changes corresponding to Erikson’s stages. The prefrontal cortex development during adolescence aligns with identity formation needs. The social brain networks that mature in young adulthood support intimacy development.

Singapore Connection

Balancing Individual and Collective Development

Singapore parents often find themselves between Western emphasis on individual identity and Asian values of collective harmony. Your mother-in-law thinks you’re raising your toddler to be selfish when you let them choose their own clothes. Your Western-educated friend thinks you’re stifling your teenager when you expect them to consider family reputation in their choices.

Erikson’s framework accommodates both approaches. Healthy identity formation doesn’t require rejecting family or culture. It means integrating these influences into authentic selfhood. Your teenager can honour family values while deciding which values matter most to them personally.

The autonomy stage illustrates this balance beautifully. Singapore children can develop independence while learning to consider others. A toddler can choose their clothes (autonomy) while learning that loud play at 11 PM disturbs neighbours (social responsibility). These aren’t contradictory. They’re both part of healthy development.

When Academic Pressure Threatens Industry

Singapore’s education system places enormous pressure on the industry versus inferiority stage. Children as young as seven compare PSLE scores and enrichment class schedules. By Primary 4, many children already feel inferior if they’re not in the “top” classes.

Erikson’s research suggests this pressure risks creating widespread feelings of inferiority in children who aren’t academically gifted. The child who struggles with Chinese but organises their room carefully demonstrates industry. So does the child who persists through difficult math problems, regardless of the final grade.

The Ministry of Education’s recent emphasis on reducing academic pressure aligns with Eriksonian principles. When Primary 1 and 2 exams were removed, it created space for children to develop industry through exploration rather than only through test performance. The removal of mid-year exams for Primary 3, 5, and Secondary 1 and 3 students continues this trend.

These policy changes recognise what Erikson knew: competence develops through experiencing success in meaningful endeavours. When “meaningful” means only “high test scores,” many children never develop the confidence that comes from industry.

Multi-Generational Households and Trust

Many Singapore families live in multi-generational households. This creates unique dynamics for Erikson’s stages. Grandparents might undermine parents’ autonomy-building efforts by rushing to help toddlers. Or they might provide additional trust-building through consistent presence and care.

A baby with multiple caregivers can build trust with several people. This is healthy, not confusing, when caregivers are consistently responsive. The infant learns that multiple people are reliable, expanding rather than fragmenting their secure base.

Open family conversations about developmental needs help. Explain to grandparents that letting the preschooler struggle briefly with their shoes builds confidence. Most grandparents, once they understand the developmental purpose, can adjust their approach.

The teenager navigating identity formation in a multi-generational household faces particular challenges. They must integrate expectations from parents, grandparents, and peers while figuring out who they are independently. This is complex but not impossible. The family that can discuss these tensions openly helps the adolescent develop fidelity to chosen values rather than rigid obedience or total rebellion.

Resources Available Locally

While Singapore organisations may not explicitly label their approaches as “Eriksonian,” many apply developmental stage principles in their work. REACH Community Services provides family support that recognises parents and children develop together. Fei Yue Community Services offers programs across the lifespan, from early childhood to eldercare.

The KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital provides developmental milestone information that aligns with Erikson’s stages. Their guidance helps parents understand what emotional and social skills to expect at different ages.

Parent support groups at community centres create spaces where parents can discuss developmental challenges. The mother worried her toddler is too clingy finds other parents navigating autonomy development. The father struggling with his teenager’s questioning finds parents who’ve successfully supported identity formation.

Why Erikson Matters to You

Erik Erikson gave parents permission to be imperfect and developing. His eight stages acknowledge that raising children while navigating your own growth is complex. The parent responding to their infant’s midnight cries while exhausted isn’t just keeping baby alive. They’re building the foundation for that child’s lifelong ability to trust others.

His framework explains why parenting feels harder at certain points. When your developmental stage clashes with your child’s, tension is inevitable. The young parent establishing their own identity (early twenties, still figuring out career and values) while raising an identity-seeking teenager faces predictable challenges. Both are asking “Who am I?” and the answers might conflict.

Most beautifully, Erikson proved that how we handle each stage affects the next, but doesn’t determine it forever. The infant who struggled with trust can build it later through healing relationships. The adolescent confused about identity can achieve clarity in young adulthood. Development is lifelong. So is the possibility of growth.

Your toddler throwing a tantrum because you put on their shoes? That’s autonomy development in action. Frustrating? Absolutely. Developmentally appropriate? Completely. Your job isn’t to prevent the crisis. It’s to support them through it in ways that build confidence rather than shame.

Understanding Erikson won’t make parenting easy. It will make it make sense. And sometimes, that’s enough.

If you’re interested in how other pioneers understood child development differently, read about Magda Gerber‘s approach to respecting infants as whole people from birth, or explore Friedrich Froebel‘s belief that play is children’s most important work. Each pioneer offers a piece of the parenting puzzle.

Further Resources

Books:

- “Childhood and Society” by Erik H. Erikson – The foundational text explaining all eight stages

- “The Life Cycle Completed” by Erik H. Erikson and Joan M. Erikson – Extended analysis with Joan’s ninth stage

- “Identity: Youth and Crisis” by Erik H. Erikson – Deep examination of adolescent development

Singapore Organizations:

- REACH Community Services – Family support programs across life stages

- Singapore Association for Counselling – Developmental counselling services

Online Resources:

- Ministry of Social and Family Development – Developmental milestone guides

- KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital – Age-appropriate parenting information

- National Library Board – Parenting collections organised by child development stage