Spring 1945. Italy lay in ruins. Mussolini was dead, the Germans had retreated, and the people of Reggio Emilia surveyed the wreckage of two decades under fascism.

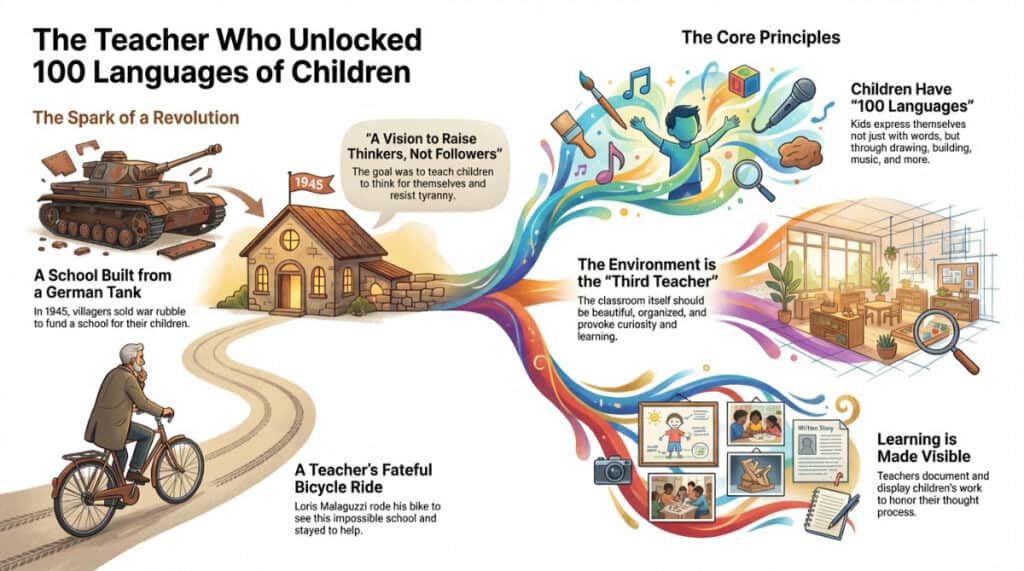

Then Loris Malaguzzi, a young elementary school teacher, heard something impossible. In the village of Villa Cella, seven kilometres away, people were building a school. Not just any school – a school funded by selling an abandoned German tank, three trucks, and six horses left behind by the retreating army.

He jumped on his bicycle and rode out to see for himself.

What he found changed early childhood education forever. Women washing salvaged bricks. Families working nights and weekends to build walls. A community determined that their children would never again live under authoritarian rule, would never again be taught to obey without question.

Malaguzzi stayed. He helped. And over the next five decades, he developed an educational approach that now influences 145 countries worldwide – including Singapore, where Reggio Emilia-inspired preschools flourish across the island.

His insight? Children aren’t empty vessels waiting to be filled. They have a hundred languages – a hundred ways of thinking, discovering, and expressing what they know. Traditional schools steal ninety-nine of them.

Early Life & Background

Growing Up Under Fascism

Loris Malaguzzi was born on February 23, 1920, in Correggio, a small town in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy. His father worked as a railway stationmaster. His mother taught in a primary school.

In 1923, when Loris was three, his family moved to the nearby city of Reggio Emilia when his father took a new railway post. Loris grew up there, attending the Istituto Magistrale secondary school.

But his childhood unfolded under Benito Mussolini’s fascist regime. From 1922 onward, Italy wasn’t a democracy. Individual rights were suppressed. Children were taught to obey the state without question. Creativity and critical thinking? Dangerous. Schools drilled conformity and obedience.

Malaguzzi later married in 1944 and had one son, Antonio, who became an architect.

Wartime Teaching

In 1939, at nineteen, Malaguzzi began training as a teacher just as World War II erupted. He started teaching during the war years, working in elementary and middle schools in Reggio Emilia and surrounding villages like Sologno, Reggiolo, and Guastalla.

Teaching in rural mountain villages during wartime shaped everything that followed. He saw poverty. He saw the effects of war on children. He saw how education could be used to control or to liberate.

In 1946, Malaguzzi graduated from the University of Urbino with a degree in pedagogy. His timing was perfect, or perhaps fate. The war had just ended. Italy was rebuilding. Everything seemed possible.

The Moment That Changed Everything

In spring 1945, Malaguzzi heard the impossible story: Villa Cella was building a school.

He rode his bicycle out to the village. Later, he described what he saw: “I find women intent upon salvaging and washing pieces of brick. The people had gotten together and had decided that the money to begin the construction would come from the sale of an abandoned war tank, a few trucks, and some horses left behind by the retreating Germans.”

The villagers explained their vision. They would build the school themselves, working nights and weekends. It wouldn’t be like the old schools – authoritarian, church-controlled, teaching blind obedience. This school would teach children to think, to question, to express themselves. To resist tyranny through independent thought.

Malaguzzi was twenty-five years old. He was moved beyond words. “It all seemed unbelievable,” he later wrote. “The idea, the school, the inventory consisting of a tank, a few trucks, and horses.”

He stayed. He helped build the school. And the trajectory of his life and early childhood education worldwide shifted completely.

Major Contributions

Building the Educational Philosophy

After experiencing the parent-run school in Villa Cella, Malaguzzi couldn’t return to traditional state schools. In his own words: “The work with the children had been rewarding, but the state-run school continued to pursue its own course, sticking to its stupid and intolerable indifference towards children.”

In 1950, after completing a six-month specialisation course in school psychology in Rome, he became Director of Children’s Psycho-Pedagogical Services for the Reggio Emilia municipality. He worked in this role for more than twenty years, supporting both schools and families.

More parent-run schools—called “nests”—sprang up around Reggio Emilia. Malaguzzi worked with them all, studying, experimenting, refining. He read widely: John Dewey, Jean Piaget, Lev Vygotsky, Jerome Bruner, Friedrich Fröbel. He travelled throughout Europe, gathering ideas. But he never imposed a fixed method. He listened to children. He watched how they learned.

The Municipal Schools Begin

In 1963, the municipality of Reggio Emilia, governed by a socialist and communist administration under Mayor Renzo Bonazzi, opened its first municipal preschool, the Robinson School. The city asked Malaguzzi to collaborate on this new educational project.

He brought everything he’d learned from two decades working with parent-run schools. The Robinson School became a place of experimentation and innovation. Teachers worked as researchers, documenting how children learned. Parents participated actively. The community became invested.

In 1971, the first municipal infant-toddler centre opened, dedicated to Genoeffa Cervi, mother of seven brothers who died as partisans fighting fascism. Malaguzzi began coordinating all of Reggio Emilia’s municipal early childhood services.

In 1972, after twenty-four drafts and eight months of work, the municipal council approved the “Regolamento”, the official rulebook laying out educational content and organisation. Parents and teachers wrote it together in a collective meeting. This was revolutionary: involving parents and teachers equally in defining education policy.

The Core Principles

Malaguzzi didn’t create a rigid curriculum. He developed guiding principles:

The Image of the Child

Children are “rich in potential, strong, powerful, competent, and most of all, connected to adults and other children.” Not empty vessels. Not beings born with original sin. Capable researchers with theories about how the world works.

The Hundred Languages

Malaguzzi believed children express themselves in countless ways, not just through spoken language but through drawing, painting, sculpting, building, music, movement, drama, and more. Schools that focus only on literacy and numeracy “steal ninety-nine” of children’s natural languages.

The Environment as Third Teacher

Parents are the first teachers. School educators are the second. The physical environment is the third. Classrooms should be beautiful, organised, filled with natural light and interesting materials. Spaces should invite exploration, collaboration, and documentation.

Documentation Makes Learning Visible

Teachers photograph, record, and display children’s work and thinking processes. This serves multiple purposes: it helps teachers understand each child’s development, it makes learning visible to parents, and it allows children to revisit and reflect on their own discoveries.

Projects Emerge From Children’s Interests

Rather than imposing predetermined curriculum, teachers observe what captures children’s attention. Projects might last days, weeks, or months, following children’s questions deeper and deeper.

“No Way. The Hundred Is There”

Malaguzzi wrote a powerful poem that became the manifesto of the Reggio Emilia approach. It begins:

The child is made of one hundred.

The child has

a hundred languages

a hundred hands

a hundred thoughts

a hundred ways of thinking

of playing, of speaking.

The poem continues, describing how schools and culture “steal ninety-nine” of these languages. They tell children to think without hands, to do without head, to listen and not speak. They separate imagination from reality, play from work, art from science.

The poem ends with the child’s defiant response: “No way. The hundred is there.”

This wasn’t abstract philosophy. Malaguzzi meant it literally. Children need access to clay, paint, wire, fabric, and wood. They need studios (called “ateliers”) with art materials. They need teachers who are themselves curious, who ask genuine questions rather than testing for predetermined answers.

Practical Applications

Understanding the Reggio Emilia Approach

Parents often ask: “What does a Reggio Emilia classroom actually look like?”

Beautiful, Organised Spaces

Walk into a Reggio classroom and you’ll notice: natural light, plants, mirrors at child height, displayed artwork, organised materials in clear containers. Everything intentional. Nothing cluttered or chaotic.

Singapore Reggio schools often incorporate local elements – tropical plants, natural wood from Southeast Asian trees, and art materials reflecting local culture.

The Atelier (Studio)

Every Reggio school has an atelier—a dedicated art studio with a trained atelierista (studio teacher). Children work with professional-quality materials: real paintbrushes, quality paper, clay, wire, light tables, and overhead projectors.

This isn’t “craft time.” It’s serious work where children use visual languages to express complex ideas.

Small Group Work

Children work in small groups of 2-4, negotiating ideas, solving problems together. Teachers intervene minimally. The learning happens through peer interaction.

Long-Term Projects

A class might spend three months exploring shadows. Another investigates how water moves. Projects follow children’s questions: “Why does my shadow change size?” “Where does rain come from?”

Teachers don’t have answers prepared. They explore alongside children, providing materials and provocations that push thinking deeper.

Applying Malaguzzi’s Ideas at Home

You don’t need a full atelier to use Reggio principles:

Provide Real Materials

Skip the plastic toys. Give your child real materials: clay (not Play-Doh), watercolours (not crayons only), fabric scraps, cardboard, wire, natural objects like shells and stones.

Real materials offer genuine learning about physical properties. Clay teaches about moisture, texture, and form. Watercolours teach about colour mixing, water absorption, and transparency.

Document Their Work

Take photos of your child’s creations. Display them at child height. Talk about what they made. Ask questions: “How did you make the tower stand?” “What happened when you mixed blue and yellow?”

This teaches children their work matters. It helps them reflect on their own thinking.

Follow Their Interests

If your child becomes obsessed with elevators, explore elevators. Visit different buildings. Watch videos. Draw elevator diagrams. Make elevator models with cardboard boxes. Read books about how they work.

Singapore offers rich opportunities: elevators in HDB blocks, MRT escalators, and Jewel Changi’s Rain Vortex. The city itself becomes a classroom.

Ask Real Questions

Don’t test with questions you already know the answer to. Ask genuine questions: “I wonder why the puddle disappeared?” “How could we make this tower taller?” “What do you notice about these two leaves?”

Real questions invite thinking. Test questions shut it down.

Create a Small Studio Space

Even in a small HDB flat, dedicate one shelf or corner to art materials. Stock it with paper, scissors, glue, tape, pencils, markers, and clay. Let your child access it freely.

Accept mess as part of learning. Put down old newspapers. Buy washable paint. Creativity is messy—and that’s okay.

Choosing Reggio-Inspired Preschools in Singapore

Several excellent Reggio-inspired options exist in Singapore:

EtonHouse International Preschool (Multiple Locations) The only education group in Singapore affiliated with the Reggio Children International Network. Runs REACH (Reggio Emilia in Asia for Children), which provides training and professional development for educators across Asia.

Odyssey The Global Preschool (6 Locations) Founded after educators witnessed “The Hundred Languages of Children” exhibition in San Francisco in 1999. Offers Reggio-inspired programs at Wilkinson Road, Fourth Avenue, Loyang, Still Road, Orchard, and Dempsey.

Mulberry Learning (Multiple Locations Islandwide) Combines Reggio Emilia methodology with Habits of Mind framework and Multiple Intelligences theory. Offers bilingual programs with strong Mandarin immersion.

E-Bridge Pre-School (Multiple Locations) Reggio Emilia-inspired programs following EtonHouse’s Inquiry.Think.Learn framework aligned with MOE NEL curriculum.

Bucket House Preschool Unique “6-4 model”—structured academic learning for 6 weeks, inquiry-based Reggio learning for 4 weeks. Created to balance Singapore parents’ need for school readiness with Reggio’s open-ended exploration.

When evaluating schools, look for:

- Ateliers or dedicated art studios

- Visible documentation of children’s work

- Natural materials and beautiful environments

- Teachers who ask questions rather than provide all answers

- Long-term projects that follow children’s interests

- Parent involvement in school life

Legacy & Ongoing Influence

International Recognition

For decades, Malaguzzi’s work remained largely unknown outside Italy. Then everything changed.

In 1980, Malaguzzi founded the Gruppo Nazionale Nidi e Infanzia; a nationwide organisation for early childhood education, creating networks across Italy.

In 1987, “The Hundred Languages of Children” exhibition toured internationally, opening at the National Association for the Education of Young Children conference. Educators from around the world saw documentation of Reggio schools’ extraordinary work.

In 1991, Newsweek magazine called the Diana School in Reggio Emilia one of the “best preschools in the world.” Suddenly, educators were making pilgrimages to this small Italian city.

Malaguzzi began travelling extensively—throughout Europe, to the United States, sharing the approach. He received numerous awards: the Lego Prize in Denmark (1992), the Kohl Prize in Chicago (1993), and the Hans Christian Andersen Prize (1994).

Death and Continuing Impact

On January 30, 1994, Loris Malaguzzi died suddenly in Reggio Emilia at age seventy-three.

But his work didn’t die with him. In March 1994, based on his idea and with support from citizens and public administration, Reggio Children was established; an international centre promoting the rights and potentials of children.

In 1996, two years after his death, colleague Susanna Mantovani organised a conference at the University of Milan: “Nostalgia del Futuro” (Nostalgia of the Future). Speakers came from across Europe and the United States to address his influence.

In 2006, the Loris Malaguzzi International Centre opened in Reggio Emilia; a place for research, innovation, and building a new culture of childhood. The centre occupies renovated historical cheese warehouses, transformed into a space for learning and creativity.

Today, the Reggio Emilia approach influences early childhood education in 145 countries. It’s not franchised or trademarked. Schools adapt the principles to their own cultures and contexts.

Influence on Educational Thinking

Malaguzzi’s work challenged fundamental assumptions:

Children as Competent Researchers

Before Malaguzzi, early childhood education often focused on preparing children for “real” school. Malaguzzi insisted that young children are already doing real intellectual work, forming theories, testing hypotheses, and making meaning.

The Power of Documentation

Making learning visible through photos, transcripts, and displays changed how teachers think about their work. Documentation isn’t just record-keeping—it’s research that informs practice.

Environment as Pedagogy

The idea that physical space actively teaches reshaped school design worldwide. Reggio schools look different—more beautiful, more intentional, more child-centred.

Parent Partnership

Involving parents as active participants rather than passive consumers changed the relationship between families and schools.

Singapore Connection

Why Reggio Thrives in Singapore

Singapore seems an unlikely home for an Italian educational philosophy. But Reggio Emilia has found strong footing here. Why?

Excellence Aligns

Singapore parents value educational excellence. Reggio schools produce exactly that, but through different means than traditional academics. Children develop deep thinking skills, creativity, collaboration, and communication.

Bilingual Strength

Many Singapore Reggio schools offer bilingual programs (English and Mandarin). The “hundred languages” philosophy naturally extends to linguistic languages. Children express complex ideas in Chinese through art, movement, and building not just through rote memorisation.

Urban Adaptation

Reggio Emilia is a small Italian city. Singapore is a dense urban nation. Yet the principles translate well. Singapore Reggio schools use HDB estates, MRT stations, hawker centres, and parks as extensions of the classroom.

Government Support

Singapore’s Nurturing Early Learners (NEL) framework emphasises play-based learning, holistic development, and child-initiated activities all aligned with Reggio principles.

REACH: Reggio in Asia

EtonHouse established REACH (Reggio Emilia in Asia for Children) as the official Reggio Children International Network member for Singapore and China. REACH offers:

- Study programs in Singapore for educators

- Study tours to Reggio Emilia, Italy

- Professional development and training

- Publications and resources

- Conference and networking opportunities

This makes Singapore a regional hub for Reggio Emilia professional development in Asia.

Balancing Reggio with Singapore Realities

Singapore parents face a tension: they love Reggio’s child-centered approach but worry about Primary One readiness.

Smart Reggio schools address this directly. Bucket House’s “6-4 model” alternates structured learning with inquiry-based projects. Other schools integrate literacy and numeracy into project work naturally.

The question isn’t “Reggio OR academics.” It’s “How do we develop both deep thinking AND foundational skills?”

Well-implemented Reggio programs do both. Children who spend months investigating light learn:

- Science (properties of light, shadows, reflection)

- Math (angles, measurement, patterns)

- Literacy (documenting discoveries, labelling diagrams)

- Collaboration (working in groups, negotiating ideas)

They just learn it through meaningful investigation rather than isolated drills.

Conclusion

Loris Malaguzzi never intended to create a trademarked method. He hated rigid systems. He believed education must evolve constantly, responsive to children, culture, and context.

That’s why Reggio Emilia works in Singapore despite vast differences from a small Italian city. The principles adapt. Children everywhere need to be seen as capable. They need environments that invite exploration. They need their many languages valued.

When your Singapore preschooler mixes paint colours to discover orange, they’re experiencing what Malaguzzi envisioned. When they build elaborate block structures in groups, negotiating engineering problems together, they’re using multiple languages to construct knowledge.

When they’re frustrated because their clay sculpture keeps falling over, and a teacher asks, “What could we try?” instead of solving it for them—that’s Malaguzzi’s legacy in action.

He rode his bicycle to Villa Cella to see women washing bricks in 1945. He stayed to help build a different kind of school, a different way of seeing children.

Eighty years later, children in Singapore classrooms explore light tables, document their thinking, work in ateliers. The hundred languages are alive. The child says: “No way. The hundred is there.”

And they are.

Further Resources

Books by Loris Malaguzzi

- “The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Experience in Transformation” (Multiple editions, co-authored with Carolyn Edwards, Lella Gandini, and George Forman)

Books About the Reggio Emilia Approach

- “Bringing Learning to Life: The Reggio Approach to Early Childhood Education” by Louise Boyd Cadwell

- “In Dialogue with Reggio Emilia” by Carlina Rinaldi

- “Beautiful Stuff: Learning with Found Materials” by Cathy Weisman Topal and Lella Gandini

- The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Approach – Advanced Reflections

Organizations and Resources

- Reggio Children (Italy): Official organisation promoting the Reggio Emilia approach – https://www.reggiochildren.it

- REACH (Singapore): Reggio Emilia in Asia for Children – https://www.reach.edu.sg

- Loris Malaguzzi International Centre (Reggio Emilia, Italy): Research and innovation center

Singapore Reggio-Inspired Schools

- EtonHouse International Preschool: Multiple locations islandwide

- Odyssey The Global Preschool: Wilkinson Road, Fourth Avenue, Loyang, Still Road, Orchard, Dempsey

- Mulberry Learning: 19 centers islandwide

- E-Bridge Pre-School: Multiple locations

- Bucket House Preschool: Unique hybrid model balancing structure with inquiry

- Primus Schoolhouse: Reggio-inspired bilingual programs

Exhibitions and Study Tours

- REACH organizes study programs in Singapore and study tours to Reggio Emilia, Italy

- “The Hundred Languages of Children” travelling exhibition occasionally visits Asia